do you believe in the existence of restaurants?

The restaurant of the future is wobbling — not like a poorly shaped nigiri, but like an entire narrative losing its binding forces. A space that once served as stage, marketplace, ritual site, and show kitchen all at once is slowly losing the self-evidence of its own existence. If you sense that the classic restaurant concept is cracking, your sensor for culinary zeitgeists probably just has unusually high resolution.

I see several tectonic shifts happening at the same time:

The first fracture appears where people optimize their daily lives. Going out to eat used to be a tiny ceremony. Today it competes with anything faster, cheaper, more individualized. The old formula — space + service + food = hospitality — is losing against ghost kitchens, meal kits, AI-optimized nutrition plans, and aesthetically tame designer snacks from vending machines that suddenly seem more charming than some city-center dining rooms.

At the same time, the value of “social space” is changing. People still want encounters, but not necessarily with servers, table linens, and a 120-minute seating time. This leads to strange hybrids: half shop, half gallery, half community hub… a trinity of new urbanity that feels more like a temporary biotope than a traditional venue. The space becomes flexible, fluid, sometimes even unnecessary.

Another rupture: radical transparency in supply chains. Guests are becoming increasingly allergic to marketing fog. They want the truth about origin, energy usage, labor conditions — and they prefer that truth without the feeling of being tricked. The old restaurant model — small stage in front, chaos in the back — is hardly tolerated by the future.

And in the middle of all this, the restaurateurs who once wanted to be magicians suddenly have to be logisticians, storytellers, ecologists, and tech architects. The profession is transforming faster than the industry can handle.

What comes next? Not an apocalypse, more a kind of evolution refusing to move in a straight line. A few possible mutations — certainly not facts, just work-in-progress thinking:

Perhaps spaces emerge that are less restaurant and more studio. Small kitchen labs where people don’t just eat but join the process: fermentation nights, R&D sessions, culinary salons. Eating as collective exploration.

Perhaps restaurants move out of the cities and into production sites, farms, urban growing spaces. Food not only “from here,” but with here — the same place where ingredients grow becomes the place where they’re cooked.

Perhaps the space dissolves entirely. The restaurant becomes a networked ecosystem: centrally produced components, combined by guests in their daily lives, supplemented with occasional events that add emotional gravity. A culinary subscription model that feels more like ritual than convenience.

Perhaps aesthetic experience grows in importance. Less decoration, more art in the original sense: meaningful, disruptive, inspiring experience. Food as cultural work, not service. This requires spaces functioning like ateliers, not like commercial operations.

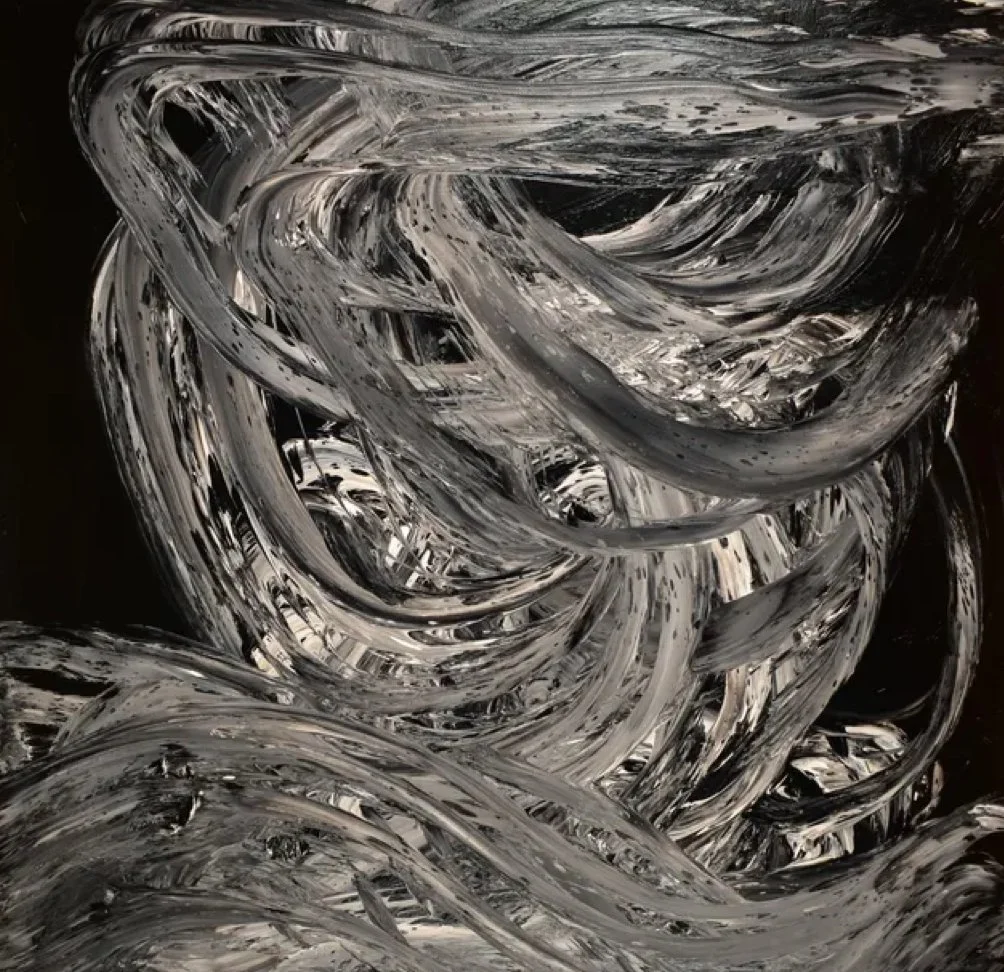

And perhaps — the most charming idea — gastronomy becomes again what it once was: a knot of human curiosity. Not a place for consumption, but for wonder. Exactly what a good kitchen has always been, if you dim the light just a touch.

The future of the restaurant isn’t dead; it’s simply shedding its old skin. If you can tolerate the tingling, something might emerge that’s closer to truth, community, and craft than much of what we see today.

If you think of transformation along the entire value chain, gastronomy suddenly becomes a large organism reorganizing its cellular structure. The future doesn’t emerge only in the dining room or the kitchen, but in every transition: from soil to seed, from supplier to production, from mise-en-place to guest communication. Change becomes less of a “project” and more of a metabolism.

One possible mental model — again, not divine truth, just a working sketch — is to treat the value chain as a sequence of leverage points. At every point, the future can be reprogrammed just a bit:

Starting point: the producers. Anyone building relationships now with farmers, fisheries, innovative fermentation labs, or urban growers is creating a culinary organism more resilient than any wholesale chain. Future-readiness grows where suppliers aren’t “suppliers” but co-developers. Co-developing varieties, preservation techniques, or secondary cuts saves resources and creates narratives deeper than any marketing story.

Next comes processing. The future here is paradoxical: simultaneously high-tech and ancient. Precise production standards supported by data (temperature profiles, fermentation curves, shelf-life models), combined with centuries-old techniques like curing, drying, pickling, fermenting. A kitchen able to scale without losing soul. The change lies in treating processing not as “back-of-house” but as atelier — a space that generates knowledge.

Logistics and distribution are where things get really interesting. For a restaurant group, every movement of a product becomes part of the storytelling. Transparency isn’t an add-on; it’s part of the offering. Packaging becomes more modular, routes more efficient, waste streams more intelligent. At the same time, logistics become emotional: guests begin to understand a carrot’s journey the way they understand a character arc in a novel. Value creation turns into value perception.

Now the dining room, which is only one chapter — not the whole book. In the future, it functions as the display window of the process. Whoever eats there sees not just a dish but an iteration: the sum of experiments, mistakes, partnerships, and acts of courage from previous steps. Change could be measured by how well an operation curates its value chain as an experience rather than hiding it.

Then the final, often forgotten stage: the afterlife of consumption. What happens to leftovers? How does guest feedback flow back into R&D? How are products reused, recycled, composted, or reborn as new product lines? Future-ready systems close loops — not for moral applause, but because it’s the smartest way to use resources.

The real pivot doesn’t lie in individual stations but in how they talk to each other. When the value chain becomes a network rather than a straight line, gastronomy suddenly becomes a learning system. You build prototypes in production, test them in the dining room, listen to suppliers, adapt logistics, and start again. It’s the same logic great kitchens have always had — just systematized.

Anyone guiding this process needs to think like a director: orchestrating scenes, harmonizing transitions, respecting the quiet intelligence of the system. The future of gastronomy emerges when each point in the chain becomes a bit braver and the system as a whole stays curious.

The next exciting steps probably lie in real culinary labs, new production ecosystems, hybrid spaces, and a culture of iterative change.

If you unroll the stakeholder map of the future, it no longer looks like a who’s-who of the restaurant industry, but like an ecosystem diagram from a biology lecture: everything connected, each organism influencing the climate of the others. A pan-Asian concept that thinks ahead must not only know this network but choreograph it intentionally.

Who belongs in it?

First and foremost, the producers. Not as “suppliers,” but as partners whose decisions shape the identity of the concept. For a pan-Asian project in Europe — especially in Switzerland — the challenge is to integrate regional producers so deeply that their products can be translated authentically into Asian culinary logics. Local beans for miso. Regional mushrooms for dashi-like broths. Ferments built on local microbial cultures but scented with Kyoto, Busan, or Chengdu. That requires courage on both sides: from farmers trying new varieties and from the kitchen laboratory recoding classics.

Then come the processing teams: chefs, R&D people, fermentation geeks, quality specialists. They are the alchemists who merge regional raw materials with Asian techniques without sliding into folklore. If production is centralized, this team becomes the pulse of the entire group. Constant learning, improving, documenting, rethinking. A pan-Asian concept gains more depth this way than many traditional restaurants that merely repeat instead of develop.

Logistics plays a quiet but decisive role. It defines freshness, speed, and transparency. A future-ready pan-Asian concept might use temperature-controlled micro-routes that move ferments, broths, and fresh components daily or several times a week between production atelier and restaurants. Logistics could even become part of the brand because it proves how seriously regionality and quality are taken.

Naturally, there are also service staff, dining-room teams, and management. They carry the stories, convey the philosophy, and must understand just how deep the value chain goes. If they don’t merely sell but explain, curate, connect, the space becomes a place of learning.

And then the guests. Not as audience but as co-creators. The more transparency, the more resonance. A modern pan-Asian concept could feed guest data directly into R&D cycles: new bowls shaped by guest feedback; fermented sauces continuously adjusted in flavor and texture; dishes born seasonally because specific producers currently have outstanding ingredients.

Finally, the small, often overlooked stakeholders: designers, artists, local communities, food-tech startups, food-safety authorities, sustainability consultants. If you treat them as part of the system, spaces become livelier and decisions more intelligent.

How could a concept look like?

Imagine a project that doesn’t try to “imitate” but to translate its way of thinking. The menu structure is modular: aromatic bases, fermented sauces, freshly composed vegetable and protein components. All prepared in a production site that works like a studio: constantly testing, tasting, improving.

The restaurants feel light, fast, artistic — not over-decorated, but clear, elegant, honest. Guests might see parts of production through screens or daily cards showing not only what they’re eating but where that dish currently sits in the value chain. The atmosphere isn’t museum-like; it’s alive: seasonal ferments on shelves, rotating artists on the walls, pop-up sessions with producers or chefs.

Regional producers appear on the menu not as marketing footnotes but as co-authors. A dish might be dangerously spicy because the local chili harvest went wild this year. Another might be available only for two weeks because that’s how long a specific mushroom ferment hits its perfect umami peak.

And the dining room becomes an extension of the atelier: you don’t just eat; you experience how local ingredients become a culinary universe that blends technique, local agriculture, and modern production into a living system.

What emerges isn’t a restaurant in the classic sense but a small ecosystem of flavor. And each link of the value chain doesn’t just have a role — it has a voice. This concept wouldn’t just be future-ready; it would be one of the rare cases where culinary identity is truly developed rather than recycled.